As the stage lures him back once again, Irek Mukhamedov talks to Ballet Position about “performing, acting, interacting, being alive.”

A dancer’s career is cruelly short. Actors can act into their 80s (look at Maggie Smith, Judi Dench), singers sing well into old age (Josephine Barstow currently hitting the top notes in the National Theatre’s production of Follies). Dancers, though? Theirs is the cruellest profession. And even years after leaving the theatre very few dancers ever stop craving the stage.

For 57-year-old Irek Mukhamedov, it’s “being on stage that’s actually quite rewarding; and it’s a kind of atmosphere, it’s a kind of the music, acting comes with the music and you live new life, maybe little bit renewed.”

We spoke in London at the end of a day when Mukhamedov had been coaching dancers at English National Ballet, where he is Guest Ballet Master. His modesty and courtesy are disconcerting in someone who reached the stratospheric heights of his career; his fluent, but accented English, peppered with the quirks of his Russian mother-tongue, is its own kind of music.

As well as coaching at ENB, Mukhamedov was preparing to return to the stage in a piece tailor-made for him by Arthur PIta for inclusion in the second iteration of Ivan Putrov’s Men in Motion, a showcase for male dancing.

“It’ll be a one man show approximately 10, 12 minutes, me on stage talking, a little bit of playing music, a little be of dancing. It’s a kind of old man remembering the past. (…)

“It’s based on classical, but I’m not the prince anymore.”

Mukhamedov – The Royal Ballet Years

What a prince among dancers he was in his heyday, though! When he joined the Royal Ballet in 1990, fresh out of the Bolshoi, he brought with him the breathtaking technique required for the heroic Soviet roles in which he’d been typecast; but London added further depth to his dancing.

“I can act. I thought I could be romantic, but coming to Royal and working with Kenneth [MacMillan] on his ballets, it actually opens up even more, to become even more romantic, I understood even better Giselle after that, so I became even more dramatic, became real actor.”

Kenneth MacMillan immediately spotted his potential. The very year he arrived at the Royal Ballet, MacMillan created a pas-de-deux for Mukhamedov and another of the choreographer’s favourite dancers, Darcey Bussell, to mark the Queen Mother’s 90th birthday.

That was the genesis of Winter Dreams, MacMillan’s take on Chekhov’s Three Sisters.

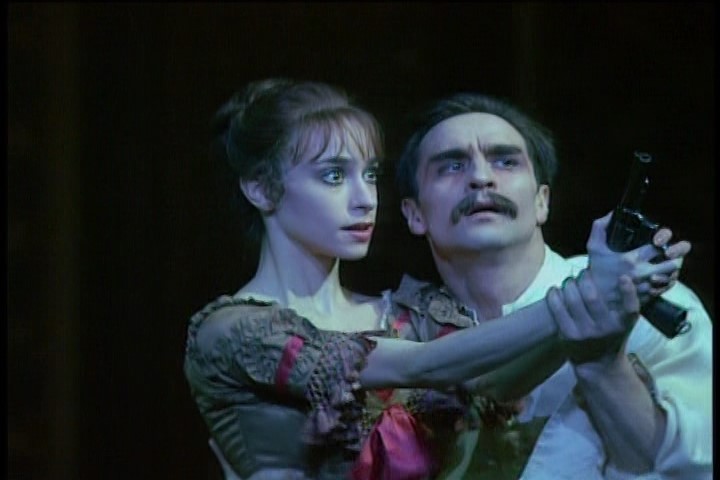

There’s a general consensus that Mukhamedov was the perfect vehicle for Kenneth MacMillan’s ballets, in particular his darkest, most complex works, where depths of human behaviour were plumbed in roles such Mayerling’s unhinged, drug-addicted, mother-fixated Habsburg Prince Rudolf, whose life would end tragically in a murder-suicide pact. Rudolf is Mukhamedov’s favourite MacMillan role.

“It’s so demanding, demanding from beginning to end, and you had to be Rudolf, you cannot be yourself even one second, even in interval, you have to be continuing with Rudolf, otherwise you lose the plot, you lose the momentum, you lose that growing role – the role grows from beginning to the end. If you switch off, it’s very difficult to come back.”

Mayerling predates Mukhamedov’s arrival at the Royal, but one role that was created on him was that of the Foreman in MacMillan’s last – and most controversial – ballet, The Judas Tree. I wanted to hear Mukhamedov’s take on the piece and on the controversy itself.

“We talked to Viviana Durante, this work was created on both of us (…) when it was created we never ever went into a situation, ‘oh, because it’s rape we have to think about it.’ No.

“It was just simply telling the story, telling the story of one of the evenings, and the boys from a working site are enjoying themselves and this is the girl that destroyed all, but at the same time she had to be destroyed too. But she’s still alive! So, that’s kind of idea (…) and of course it’s a Kenneth MacMillan, we didn’t say, ‘well, we’re doing Romantic ballet’”.

Interviewed about The Judas Tree when first asked to dance The Foreman a few years back, Carlos Acosta said, “it messes with your head!” Did it mess with Mukhamedov’s head, I wondered?

“No, not really, it’s not messed, it’s just you go into the role, into the character. It’s very difficult afterwards to smile immediately, I can only be back to myself by next morning. With Prince Rudolf, that took even longer, because there’s even deeper to go.”

Mukhamedov – After the Royal

Mukhamedov was let go by the Royal Ballet in a staggeringly ungracious way in 2001. He seems not to bear grudges, though, and has returned to coach the current crop of Royal Principals, most recently for the programmes marking the 25th anniversary of MacMillan’s premature death backstage, while Mukhamedov was dancing Rudolf.

Equally, he’s back coaching at ENB, even though his full time association with the company ended in the summer.

In the studio I’m told Mukhamedov is a very hard taskmaster towards both dancers and pianist. Is that true?

He laughs. “Well, this comes with the job. We can be a little bit relaxed, but when we do, we have to do, otherwise the body will never remember. The mind will understand probably, but the body must remember!”

There is perhaps one grudge he bears. After his abrupt and rather acrimonious departure from the Bolshoi, amid the upheaval caused by the fall of communism and the disintegration of the Soviet Union, he never went back.

“I think Russians are hard people, they probably ‘knew,’ like I ‘knew’ when Rudolf [Nureyev] left, I learned afterwards he is actually traitor, he defected, he betrayed our country, so probably the rest of the people think, me too, I’m a traitor, I betrayed the country and everything. But in the end we continued [carrying] the Russian flag of ballet up high, not hating Russia.”

Nor was he asked back. As he is keen to point out, when they left the Soviet Union his wife Masha was pregnant with their daughter, Sasha. So, Mukhamedov’s own family started in the UK.

Asked about Sasha Mukhamedov, now a Principal with Dutch National Ballet, he tries (and fails) to sound as though he’s not bursting with pride…

“I’m very happy for her success and her progress whatever she’s doing. A lot of things is in the genes. She’s just done Mata Hari, (…) she was very good acting, technician, dancer and all this, so it’s good.”

There’s also a son, now 21, being coached by his mother in her private teaching studio in France, where the Mukhamedovs now reside.

Mukhamedov – The Future

So, after an illustrious dancing career, and spells as Artistic Director in Greece and Slovenia, as well as the occasional return to the stage, what’s next for Irek Mukhamedov?

“So far I’m freelance, I’m enjoying myself, I’m travelling a lot. I started as a freelance from August, so I’ve been in Uruguay, I’ve been in Korea, I’ve been with the Royal Ballet and now ENB.”

Next it’s Amsterdam, where he’s looking forward to seeing his daughter. Any thoughts of retirement?

“No, no, no, no way!… I don’t know, [only] if somebody eventually say, I don’t need you anymore…”

They’d be fools to…

E N D

by Teresa Guerreiro

Men in Motion is at the London Coliseum on 22nd and 23rd November at 19:30