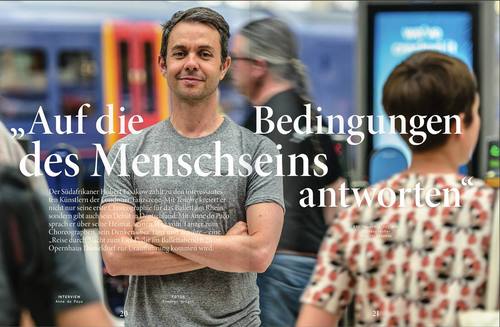

As he prepares for his first major international commission in Düsseldorf, Hubert Essakow talks about life as a freelance choreographer.

Call it serendipity.

Had the great Lynn Seymour not been friends with Hubert Essakow’s favourite actress, Sara Kestelman, he may never have made it to Düsseldorf.

But they were friends, and Lynn Seymour came to see Kestelman playing a speaking role in Essakow’s Ignis at London’s Print Room.

Essakow takes up the story:

“She loved it and immediately said to me, ‘I think you’d work really well with this company in Düsseldorf.’“

The company is the 45-strong Ballett am Rhein, described by Die Welt newspaper as “Germany’s most exciting dance company” under its dynamic director, Martin Schläpfer.

“Lynn had just been there to stage [Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of] Isadora [Duncan] and got on really well with the Director. She said, ‘I’m going to contact him; I think you’ll work well together.’”

Lynn Seymour was right, and the result was Tenebre, which will have its première in Düsseldorf on 28th May.

“It’s taken from a couple of pieces of music by Bryce Dessner. He’s an American contemporary composer and wrote Tenebre for the Kronos Quartet.

“Tenebre is a ceremony that happens at Easter to signify the death of Christ and so the extinguishing of light. But Dessner’s reversed that process, so he goes from darkness into light.”

Essakow’s own Lighting Designer, Mark Doubleday, is working on how much and how little light the stage can take to illustrate that process; and the choreographer is keen that the costumes should add an extra dimension to the work.

“Tenebre also means “shadows”, so I love this idea of a shadowy environment, the obscurity, the Delphic quality, strange, unknown feelings, getting to be something that’s – what is the word? – transcending. “

Martin Schläpfer gave him creative freedom with just a couple of stipulations: that he should use the theatre’s own orchestra live, and employ as many of the company’s dancers as possible.

Essakow had only ever worked with small groups of dancers; this proved a challenge.

“There is a sort of narrative running through, of three main couples who go on this journey from darkness to light. So I had to choose some soloists, and they’re a company of soloists really, so the choice has been really difficult.”

Essakow’s Path to Düsseldorf

Hubert Essakow has been choreographing for a while, but his stage career started as a purely classical dancer, first in his native South Africa and then as a member of Britain’s Royal Ballet for 10 years.

He says he always felt the pull of choreography, but for a long time didn’t have the means to create his own work.

“We were never really taught that at school. In the Royal Ballet there were never opportunities. Now there are loads of opportunities, but then it was always the same people choreographing.”

The breakthrough came when he joined Rambert.

“The environment was right. It was very creative!”

Once his creativity was unleashed his very first piece was a riot of experimentation – and provocation.

It was called What Rainbow?

“My partner at the time was a composer. He was quite a controversial composer, quite avant-garde and he based the lyrics on porn, he’d taken a lot of porn trailers from the 70s, so it was incredibly controversial! There was a song that my partner had put together, which was incredibly rude.”

He laughs, still relishing the memory of the piece’s impact and the fact that some of the audience walked out in shock.

His next piece was inspired by Britney Spears, who at the time was having a very public breakdown.

“It was a car crash,” he states candidly. “But somebody from the BBC saw it and we actually made it onto BBC News, because it was so topical at the time…”

More laughter, this time slightly sheepish: “I’m not sure it was quite Rambert’s style, to be honest. I think it was just me wanting to be different, theatrical.”

As he experimented, Hubert Essakow gradually found his voice. His choreographic language is a harmonious blend of classical ballet and contemporary dance with something very much his own thrown in.

No longer interested in simple provocation, he now seeks inspiration in weightier subjects. His latest piece, Terra, is the final part of a trilogy based on the elements, the previous ones being Flow, for water, Ignis for fire.

“Ignis was about loss, fire, and betrayal… I’m quite drawn to darker and intense feelings. I like human feelings… somehow to map out our journeys as human beings, and that’s the great thing about dance: it can talk in a language that’s quite instinctive, not intellectual.”

Terra was ultimately about “survival;” but more than that it pointed to very topical concerns: migration, ecology and the search for a home in our common planet, our mother earth.

“Music is the big thing. (…) But with Terra, because I was working with Gareth Mitchell [sound designer at the Print Room] for the sound, I wanted as little music as possible, because I think dance can exist without music.”

Like all of Essakow’s pieces, Terra used the spoken word, in this case an especially commissioned poem by the Nigerian writer, Ben Okri, snatches of which were skilfully blended in the work’s sound architecture.

Beyond his need to experiment, the inclusion of the spoken word is to some extent dictated by the conditions in the Print Room, now based at Notting Hill’s Coronet, where Hubert Essakow is Artistic Associate.

The Print Room is small and intimate: “it’s not like a dance space, it’s more like a theatre space.”

It is, in fact, a unique and inspirational space. The Notting Hill Coronet started life as a Victorian playhouse. Its stage hosted the likes of Sarah Bernhardt. In its Belle Epoque days it was a regular haunt of royals and bohemians.

For most of the 20th century, though, the Coronet was a cinema, and it slowly fell into disrepair until it was taken over by The Print Room in 2014.

It’s now in the middle of a five-year restoration project aimed at returning it to its full glory.

In many ways it’s been a perfect setting for Hubert Essakow’s work; and the support of the Print Room has been crucial in his development as a choreographer.

So far, though, choreographing has not provided a living wage; and Hubert Essakow does a lot of teaching on the side. The Düsseldorf commission is a step in the right direction, but should his choreographic work take off, he would still like to continue teaching.

“I think choreographers should be able to teach. Balanchine took company class – that’s how you get to know the dancers. In Germany, Martin Schläpfer teaches the company. I do enjoy teaching, passing something on that might help in some way.”

We’re back where we started: Düsseldorf, and what Essakow stresses was Lynn Seymour’s “incredible generosity” towards him.

“She said to me, ‘Ashton and Nureyev were so generous to me, it’s great to have the opportunity to be generous in my turn to someone else.’”

Hubert Essakow hopes one day he, too, will have the opportunity to show generosity to the next generation. He can think of no better way to repay Lynn Seymour.

E N D

For a full list of all out blogs click here