Maina Gielgud talks about her career, a gift from Maurice Béjart, and ballet’s need to rediscover the joy of movement

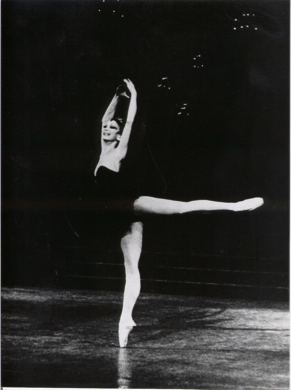

Few dance careers can have been more diverse than that of British ballerina Maina Gielgud.

Ballet de Roland Petit… Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet… Staatsoper Ballett Berlin … Ballets du XXème Siècle Maurice Béjart… The Australian Ballet… these are just some of the companies with which she danced in a 20-year career spanning pretty well all of Europe, plus the Americas, Africa and Australia.

All because she had inside her an overwhelming “need to dance.”

“In the old days, dancers were not paid well,

didn’t have any security,

didn’t have health insurance,

didn’t even have their shoes paid,

let alone their classes;

so, if you became a dancer,

it’s because you really wanted to

dance.”

Even after she hung up her dancing shoes her life-long passion for ballet didn’t wane.

She became Artistic Director of the Australian Ballet – the company’s longest serving director to date – and then briefly held the same position in the Royal Danish Ballet. She is Artistic Adviser for the Hungarian National Ballet.

And Maina remains in great demand internationally as Guest Teacher, as well as being regularly invited by major companies across the globe to mount her own productions of the classics.

Most recently, over Christmas, she recreated Coppelia for students of the Australian Conservatoire of Ballet, Melbourne.

By all accounts, the standards of Gielgud’s Coppelia were so high one reviewer wrote it was hard to believe it was a student production.

Standards are very much Maina Gielgud’s thing

“I find nowadays there is little talk of style or understanding of it in coaching in general,” she says.

Another problem is that many dancers appear to have lost a feel for pure movement.

“I’m starting to think that they see dance as a succession of photographic possibilities.

“I think they’re thinking about the next Facebook photo that they can put up, the best line, the highest leg and the odd video of triple fouettés, but the sense of dance so very often gets almost completely lost.”

She’s fighting her one-woman battle against this trend:

“I find that more and more even when I’m teaching now, I talk about the upper body, I talk about the head, the use of the eyes in just classical combinations, the épaulement – the lost art of épaulement! – and more and more a sense of movement and coordination.”

Contemporary dance technique, with its different awareness of body weight and how to use it, could be extremely useful to ballet dancers, Maina Gielgud feels, if only they were able to harness it.

“In contemporary they feel free, they can move, they have learnt how to use their weight, but unless it’s demonstrated to them (…) they simply don’t think of utilising the tools that they have in contemporary in their classical, and more’s the pity.”

She only came fully to realise how useful contemporary technique could be to ballet dancers relatively recently; but her first brush with contemporary came in the late 1960s, when she was with Béjart’s company.

“There was a wonderful contemporary black dancer called Dyane Gray-Cullert. And she had worked with Lester Horton and she proposed to some of us to do some Horton Technique classes.”

Horton Technique emphasizes a whole body, anatomical approach to dance, that includes flexibility, strength, coordination and body and spatial awareness to enable unrestricted, dramatic freedom of expression.

“I’d only ever heard of ‘hold your back, hold yourself straight’ and I’d never discovered that there were so many things you could do with your back, and indeed your weight.

“That was a really big discovery for me, utilising different aspects of your back, your neck and different parts of your body that people don’t talk about in classical training even though some of the greatest dancers do use them.”

A Gift from Maurice Béjart

Her four-year stay with Ballets du XXème Siècle Maurice Béjart, one of the longest sojourns of her dancing career, brought the young Maina Gielgud more revelations … and a bitter-sweet parting gift. Béjart liked her:

“Oh yes! And I adored him!

“It was when I saw Béjart’s ballets in Avignon that it struck me that indeed ballet, dance, was very serious and could communicate important things to do with the present, to do with philosophy and religion, way beyond what at the time I thought perhaps classical ballet could.

“[I realised] he always had something to say which was important to him and obviously important to all the dancers in the company; and huge audiences responded to that, all kinds of people who would never be seen dead at a classical ballet performance.”

Maina decided she must join the company; but had to wait a full year for a place.

She was fascinated by what Béjart was creating for his male dancers and dared hope he’d create something as extraordinary for a woman.

Béjart’s great gift, when it finally came in her last summer with the company was, however, something quite unexpected.

“Just before we broke up Maurice said to me before a performance, ‘Oh Maina, if you dance very well today I’ve got a surprise for you at the beginning of next season.’

“He came round afterwards and said, ‘I want to create a solo for you. We’re going to go to the US and do a season at the Brooklyn Academy next January. In September when we come back [from the Summer break] we’re going over to do a little preview for publicity.

‘I’m going to take four of my dancers and I realised that I have no solo for a woman that stands on its own. So I want to do for you the later scene from Lady Macbeth with the recording of Maria Callas singing it.’”

Maina Gielgud laughs heartily at the memory.

“As you can imagine, in summer I thought all my Christmases had come at once.

“First day back, my name was up on the board, it just said Maina, studio whatever. I went into the studio about an hour before to warm up and be ready.

‘[For music] he always used tapes, the old reel-to-reel, so there was (…) the music man preparing some tapes, and he was making a bloody awful noise and squeaking and screeching.

“Finally I said to him, ‘look, could we put on the music for what Maurice is going to start working on for me later on?’ and he looked at me and he said, ‘oh, but this IS the music!’

At that point Maurice Béjart walked in. Not a word about Lady Macbeth or Callas…

“He made this solo in two sessions. I don’t think I ever had the courage to ask him, but I think I cried all night that I had to dance to these squeaks and groans.”

The piece became know as Squeaky Door (La Porte).

She can see the funny side now…

“We went to the US and I did it for the publicity preview and that was that. It was quite amusing and it was quite fun, but certainly it wasn’t Lady Macbeth.”

The tale doesn’t end there. Maina was exceptionally allowed by Béjart to do a guest performance for Rosella Hightower’s company – Béjart, Hightower and Gielgud were all good friends. Hightower had heard of Squeaky Door and asked to see it.

Next thing Maina knew, Rosella Hightower was on the phone to Béjart.

“She said, ‘I’ve got a gala, could Maina do it for the gala?’

“And when I left the company, which was soon after, Maurice gave it to me as a present and said I could do it wherever I wanted to.”

So many memories of a dancing life lived to the full – and all because Maina Gielgud had that all-consuming “need to dance.” That, she feels, is what auditions for companies and indeed ballet schools should be able to assess as part of their selection process.

Do applicants have the right physique? Good feet, good turn out? Fine! but “do they really, really want to dance more than anything else?”

E N D

For a full list of all our blogs click here

I am a retired professional ballet/Graham modern dancer, now directing a dance program in Texas. I can Completely identify with the words & lessons of Gielgud… I myself instruct ballet dancers, using full anatomical approach, as in contemporary dance, and I have always had that deep, driving “need to dance!!”