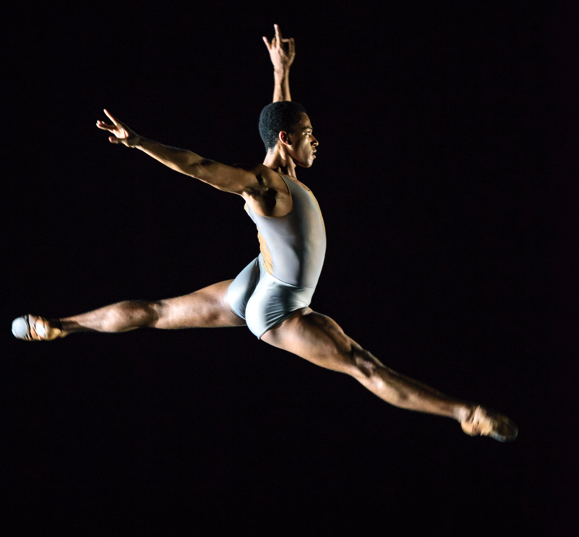

The Royal Ballet’s Solomon Golding discusses his abiding passion for ballet and his determination to inspire audiences with his art.

Solomon Golding is an extremely personable young man: polite, intelligent and bursting with self-belief. Extremely articulate, words pour out of him with contagious enthusiasm.

When he smiles – which is often – his eyes shine, be it with amusement, wonder, or the sheer pleasure of talking about ballet.

Oh, and he is also a very talented dancer, at 24 years-old in his fourth season with the Royal Ballet – the first British male mixed-race dancer to break into Britain’s premier ballet company.

“If I’m not doing ballet I don’t know whatever else I’d be doing,” he says, and the mere thought casts a brief cloud over his open countenance.

As a child he was “the little performer: since I could walk I was always dancing around, and I loved music and pop culture.”

Not ballet, though, despite the passion his Scottish Mother’s family had for the performing arts.

“My Grandma really enjoyed opera, had been to the Opera House; and my Mum was in love with Rudolf Nureyev! (…) but we were never interested, we were like ‘oh yeah, whatever, Mum…’”

Then came what he describes as his “eureka moment.”

He was about seven-years-old and his family was living in Ghana, West Africa, at the time.

“There wasn’t much in the way of television, entertainment in the sense that we know it in the West, so if you weren’t outside, there wasn’t really much for us to do (…)

“My grandma [in Britain] used to send over VHS [tapes] that she recorded, like Christmas specials. So, I think it was a Christmas Wallace and Gromit and she left the tape to record the whole way through, and the next thing on was Romeo and Juliet with the Royal Ballet, a Christmas broadcast.

“And I sat and watched the ballet and was like, ‘what is this amazing art form?’”

That Romeo was danced by the Cuban superstar Carlos Acosta was a plus. Beyond that, Solomon felt very strongly that the whole thing just “made sense.”

“The physical movement of the men and the women was just so appealing to me, it just looked so elegant and so logical for me: it made sense to see people move in that way.”

When the family returned to Britain and settled in Cambridge, Solomon and his two siblings enrolled in Octagon studios, a performing arts school in nearby Ely.

“My older brother did drama, he also did dance, my sister did dance, I did dance, so it was like a whole family kind of venture. My Mum loved it because she had so much history with the ballet and finally she could share it with someone!”

His Father comes from Jamaica. Was he equally supportive?

“Jamaica is well-known for being quite a homophobic country and me growing up and listening to the music that was coming out of Jamaica, reggae, and also their pop music, I mean, rap is very homophobic… I’m gay, so it was a weird thing.

“But my Dad was very supportive, because he just wanted the best for us and he saw that I was talented.”

So talented, in fact, that within six months he had auditioned for, and been accepted by Royal Ballet Junior Associates. Then he entered the Royal Ballet School.

It was a rude awakening.

“I wasn’t fully prepared for some of the things I would face in those environments.

“Suddenly it all became very serious, and it became, you know, life and death. And I’m saying, ‘hold on, I just wanted to dance!’

“The kind of school that I came from and the teacher that I had, Helen Pettit (…) – I’m still coached by her, I see her often – it was a more freeing experience of dance, I wasn’t afraid to make a mistake. It was all very exploratory: ‘try and do pirouettes, if you can do it, great, if you can’t, we’ll work on it.’”

Solomon found the strict discipline of the august Royal Ballet School stifling. And other things jarred, too:

“I’d seen [the film of] Billy Elliot as well, and that was another thing that resonated with me, because I am working class and he was as well (…)

Also being an outsider in an institution which is seen as… you know?… quite closed? (…) I think I saw that quite a lot in things like in Billy Elliot and the kind of stereotypes, the board at audition and all that, which I think I wasn’t prepared for and didn’t expect.”

He is keen to stress he didn’t encounter racism as such; it was just that he, a stubborn teenager used to doing things his own way, and the formal, traditional, ‘top-down’ school were a bad fit.

Still, after eight years he graduated; but things didn’t become easier.

“I did about 13 or 14 auditions, I didn’t get a job anywhere. I just felt so betrayed by it all, I worked so much for the company, I took it seriously! I mean I took my work very very seriously, and yeah, what’s going on?

“So in my last audition I went to New York City and the audition was for Hong Kong Ballet and I got the job and so I said, I’m going to Hong Kong. And people said, are you crazy?

“I was 19, and I was like ‘I want to do ballet, I don’t know how much I have to say this, I want to do it!’”

Hong Kong was a mixed experience. Dancing was rewarding, and he relished being given solo roles. Audiences, though, he found dispiriting, more interested in finance and luxury brands than ballet and the arts in general.

The way out after just a few months was a job offer by Boston Ballet; but disaster struck when his American visa application was turned down.

So, Solomon found himself back in London with no job and facing a new round of auditions. Ever determined and resourceful, he emailed Royal Ballet Artistic Director, Kevin O’Hare.

“Could I come in and take some ballet classes just to stay in shape. He was like, ‘sure, come in, I’ll have a look at you as well, if you want,’ and I was like, ‘well, sure!’ (laughs) and I was in for a week and they gave me a job.”

He calls it serendipity:

“I went round the world [only] to come back again!”

And so he became the first mixed race British male dancer in the Royal Ballet. Being the first of anything anywhere is often a mixed blessing. Does he feel it puts an extra weight on his shoulders?

“I’d rather have an extra reason to stay on the path I’m on and do it responsibly than have a million reasons to quit!”

Having said that, he’s aware change doesn’t come easily in this “most stereotypical of art forms:”

“What is our idea of Prince Charming, for example? I feel like it’s not so much racism, but the way things have been done for so long.

“The image of what the pinnacle male prince should look like can be quite restrictive for anyone else who doesn’t look like that.”

Contemporary ballet provides a new freedom: he enjoyed being part of the recent Wayne McGregor Triple Bill at Covent Garden, for which he says he had good feedback.

Versatile as he is, though, his passion remains classical ballet. And within classical ballet, he wants to explore the big acting roles.

“There are some really great actors here [at the Royal Ballet], really amazing actors I can learn from, like Laura Morera – she’s just like such a consummate actress, it’s amazing to see. This is something I hope to achieve…”

Asked where he hopes to be in five years Solomon suggests, “towards the top ranks of this company?”

I promise I’ll be in the audience for his first Romeo… and he leaves the interview room to get on with the rest of his dancing day: a rehearsal of new choreography and finally an evening performance of McGregor’s work.

He just can’t wait to get on with it….

By Teresa Guerreiro

Solomon Golding is performing in The Nutcracker, which runs at Royal Opera House until 12th January and will be relayed live to UK cinemas on 8th December.

E N D